~ for English scroll down

Działająca współcześnie artystka inspiruje się swoimi poprzedniczkami. Nie ukrywa tego, lecz przeciwnie – otwarcie sygnalizuje ów fakt w każdej z poświęconych im prac. Historie i dzieła Katarzyny Kobro, Erny Rosenstein oraz Marii Jaremy wpłynęły na powstanie realizacji ujętych w cykle Historia o Katarzynie, Erna, Kolekcja (dla Marii). Każda z wymienionych artystek była twórczynią awangardy, każda żyła w dwudziestym wieku, a ich losy zostały naznaczone przez najstraszliwsze wydarzenia: wojny i ich konsekwencje, śmierć bliskich, nędzę i wysiedlenia. Złe czasy nie sprzyjały twórczości. A jednak one przy sztuce pozostały powracając do niej nawet w najgorszych momentach. Sztuka jako terapia? Z całą pewnością nie. Liczyło się ocalenie czegoś dalece większego. Dodatkowo jeszcze, twórczość każdej ze wspomnianych, już po ich śmierci, czekała długo na nową interpretację, nowe spojrzenie, zamknięta w oczywistościach i gotowych odczytaniach.

Autorką, która wpuściła dorobek poprzedniczek w krwioobieg dzisiejszej sztuki, jest Małgorzata Malwina Niespodziewana. W ich postawach widzi ona przede wszystkim wrażliwość, ale i siłę życia mimo cierpienia, przynoszonego przez świat zewnętrzny i – jak już wspomniałam – zasadnicze przekonanie o sztuce jako ratunku dla człowieczeństwa w granicznych momentach. Artystyczne życiorysy wymienionych autorek zawierają bowiem następującą sekwencję wydarzeń: po początkowych sukcesach przychodzi wojna i związane z nią zło, naznaczające wszystko i wszystkich. Potem zaś – nie ma odkupienia, nic nie jest już takie jak było i trzeba żyć dalej z ciężarem pamięci.

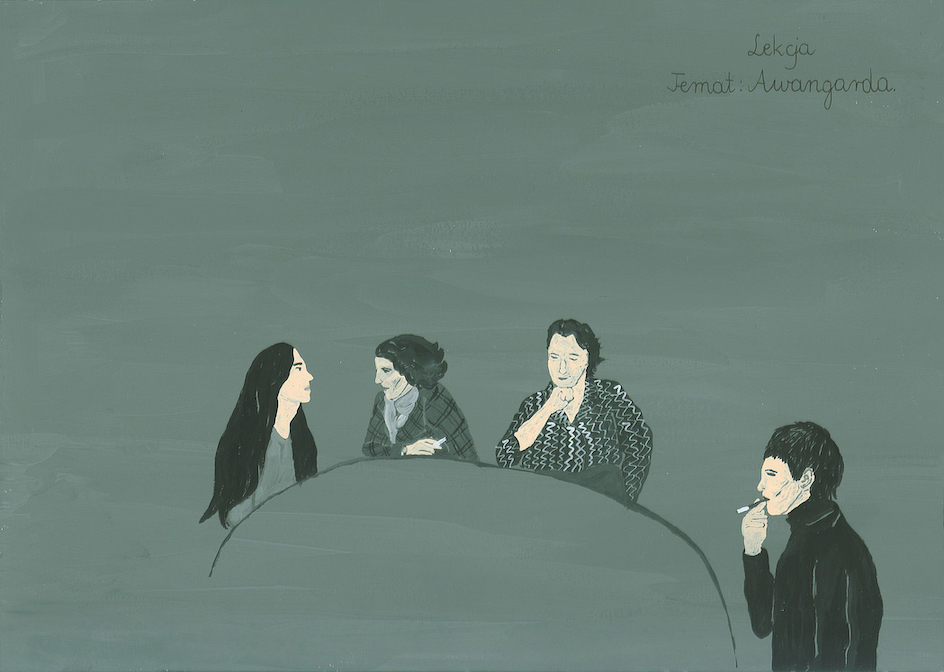

W sposobie, w jaki Niespodziewana relacjonuje postawy swoich bohaterek, pojawia się gest przekory w stosunku do wysokich, modernistycznych stylów mówienia o artystach, w których nie do pomyślenia było opowiadanie o sztuce poprzez biografie, które utożsamiano z „plotkarstwem”. Owszem, istnieje w naszej kulturze rozwinięty nurt biografistyki, który cieszy się własnymi prawami i schematami fabularnymi. Prace Niespodziewanej to przeniesienie w pewien sposób tego nurtu w niezbyt przyjazny mu żywioł sztuk wizualnych.

Strategia jest z gruntu ponowoczesna. Bazuje wszak na przekonaniu, że nie wymyślimy już nic nowego i możemy tylko miksować gotowe symbole w coraz to nowe konstelacje. Niespodziewana akceptuje fakt, że stoi na ramionach olbrzymek. Jej poprzedniczki wypracowały język nowoczesności, który ona – ich następczyni – może dzisiaj co najwyżej zastosować. Zjawisko wyczerpania nie musi jednak oznaczać słabości. Przywracanie żywej pamięci poprzedniczek jest przecież także pracą u podstaw: tworzeniem kobiecej wersji historii sztuki, czyli herstorii, tkaniem wątków matriarchalnej genealogii artystycznej. Jest też budowaniem przez artystkę własnej, bezpiecznej przystani, gdzie nikt nie zakwestionuje jej działalności. Gest Niespodziewanej oznacza więc tworzenie wspólnoty artystek: przyznanie się do matek-patronek-awangardystek, lecz także wsparcie dla współcześnie uprawiających sztukę sióstr-koleżanek.

Sięgnięcie przez Niespodziewaną po dorobek pionierek awangardy zbiegło się w czasie ze wzrostem zainteresowania rolą i miejscem artystek w polu sztuki. Te co najmniej od początku lat dziewięćdziesiątych wychodzą z cienia, w jakie zagnała je historia sztuki, a proces wzmacniania pozycji tworzących kobiet, mimo przeszkód, nie ustaje. Prace Małgorzaty Malwiny Niespodziewanej stanowią część zachodzących na naszych oczach zmian i zarazem dowód, że dorobek pionierek awangardy można czytać z zainteresowaniem także i dzisiaj. Oczywiście, czytać w inny sposób niż dotychczas, trzeba sięgnąć przecież po konteksty twórczości – tło biograficzne i historyczne, stosować wypracowany przez siebie eklektyzm interpretacyjny. Malwina Niespodziewana wykorzystuje zatem wiedzę biograficzną, ale także schematy narracyjne używane przy relacjonowaniu losów artystek. Świadomie sięga do zasobów kultury popularnej z takimi jej gatunkami, jak komiks czy książki dla dzieci. Odtwarza emocjonalną aurę epizodów biograficznych, tworzy jakby wewnętrzne portety, posługując się po wirtuozersku językiem formy. Przy Kobro relacjonuje etapy nieszczęśliwie zakończonego życia, przy Rosenstein skupia się na aurze jej świata wyobrażonego, przy Jaremiance poprzez materiał i formę podkreśla elegancję i kruchość awangardowej sztuki tworzonej na przekór czasowi, w którym artystce przyszło żyć.

W 2008 roku Niespodziewana przywołała postać Katarzyny Kobro. Ale nie nowatorski dorobek artystyczny rzeźbiarki stanowił główny obiekt zainteresowania. Dorobek, stawiający ją w pierwszym rzędzie mistrzów i mistrzyń pierwszej awangardy, został zestawiony z dramatycznymi kolejami losu. Tworząc prace o Kobro, artystka odwróciła zwyczajowy sposób relacjonowania biografii. Los rzeźbiarki nie usprawiedliwia jej twórczości, przeciwnie: sztuka powstaje wbrew życiowym okolicznościom. Niespodziewana celowo oparła się na relacji córki artystki, mimo że Nice Strzemińskiej zarzucano brak obiektywizmu. Pamiętajmy jednak, że Kobro, która do lat dziewięćdziesiątych pozostawała znana tylko w kręgu specjalistów, zyskała pośmiertne uznanie przede wszystkim dzięki staraniom córki, wspartej przez Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi. Niespodziewana korzystała z tych dokonań, lecz prowadziła także własne poszukiwania. Opowieść Niki jest dla niej znakomitą bazą do snucia opowieści, bowiem tematem Historii o Katarzynie uczyniła relację matki-artystki i córki, która pragnęła ocalić o niej pamięć. Jest to historia Katarzyny widziana oczyma Niki.

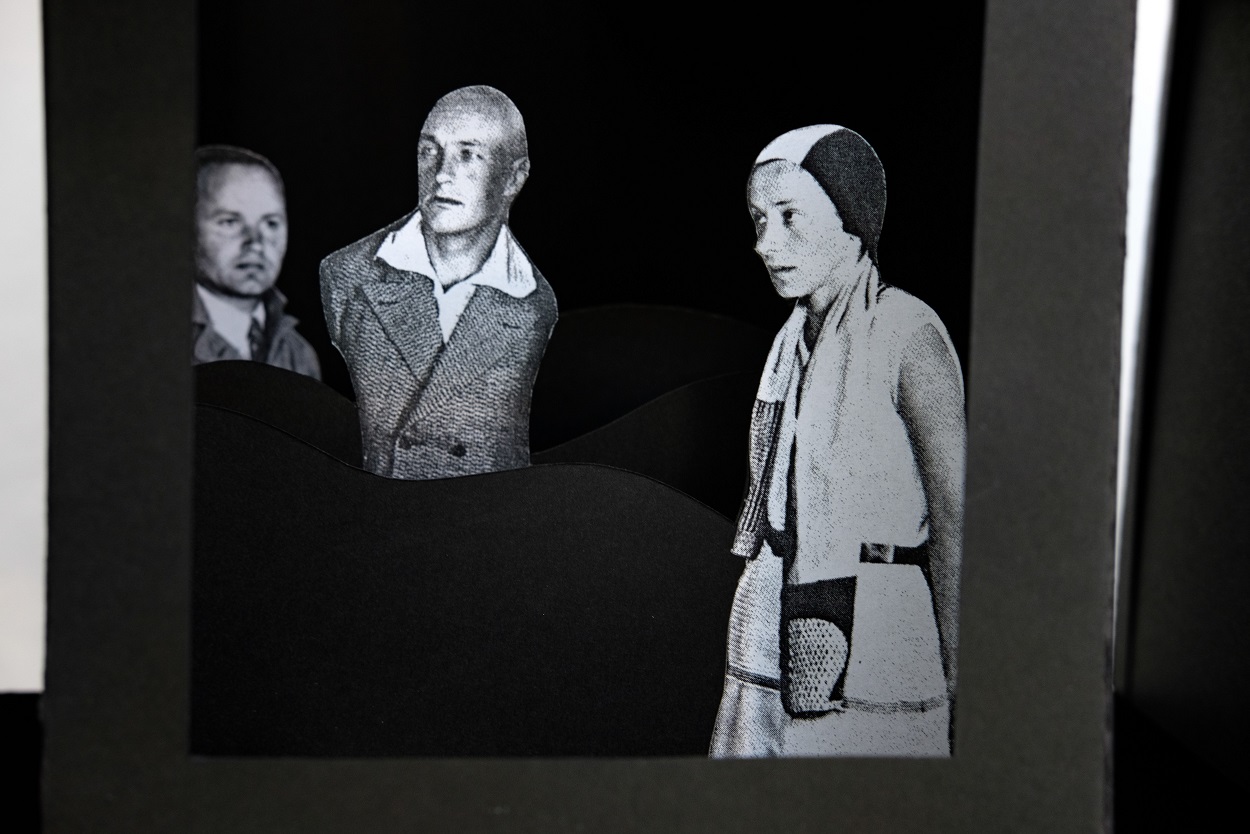

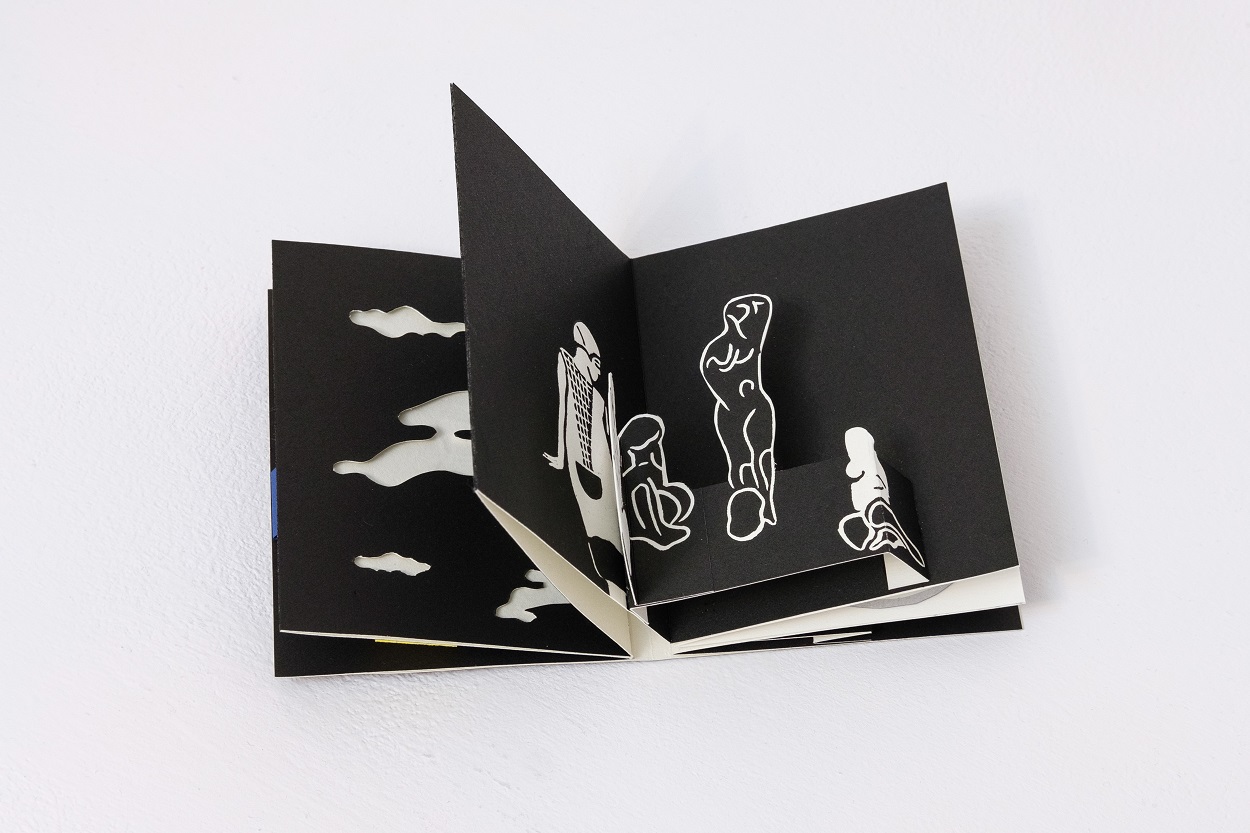

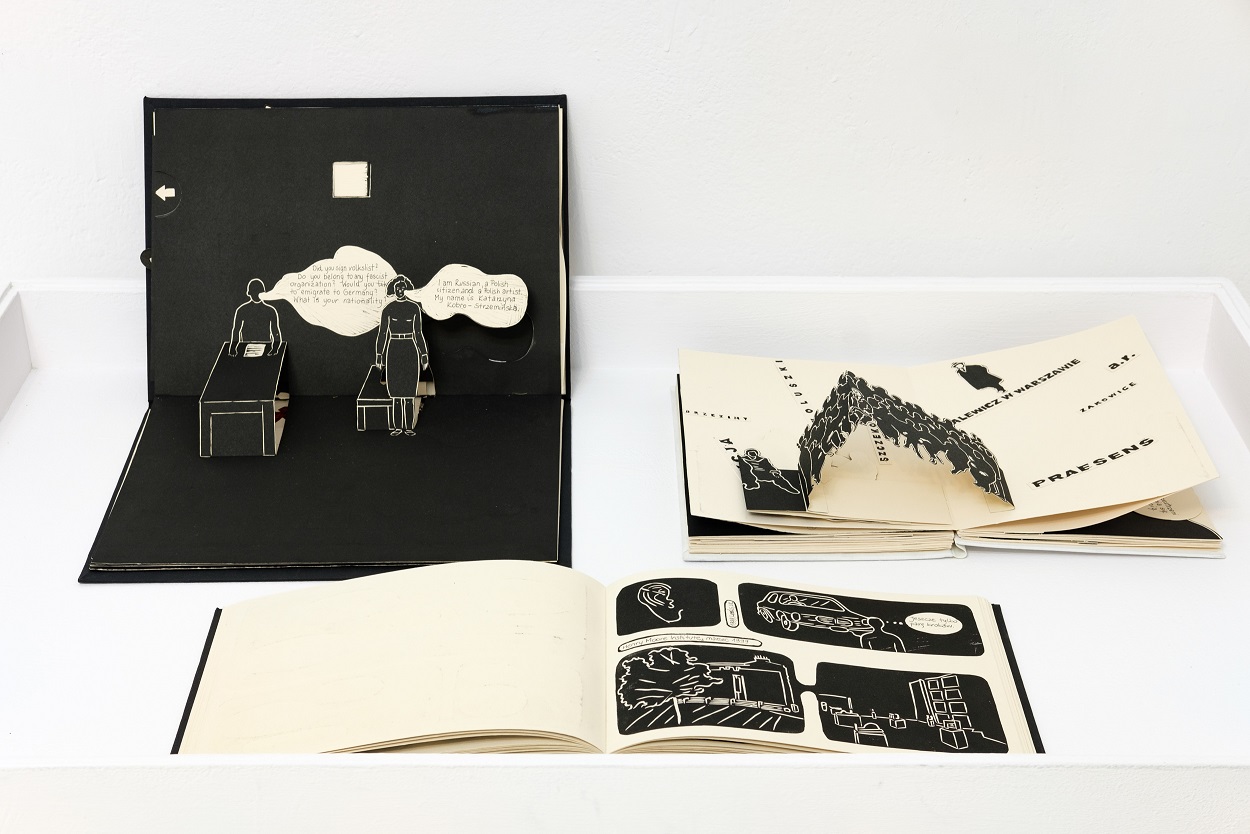

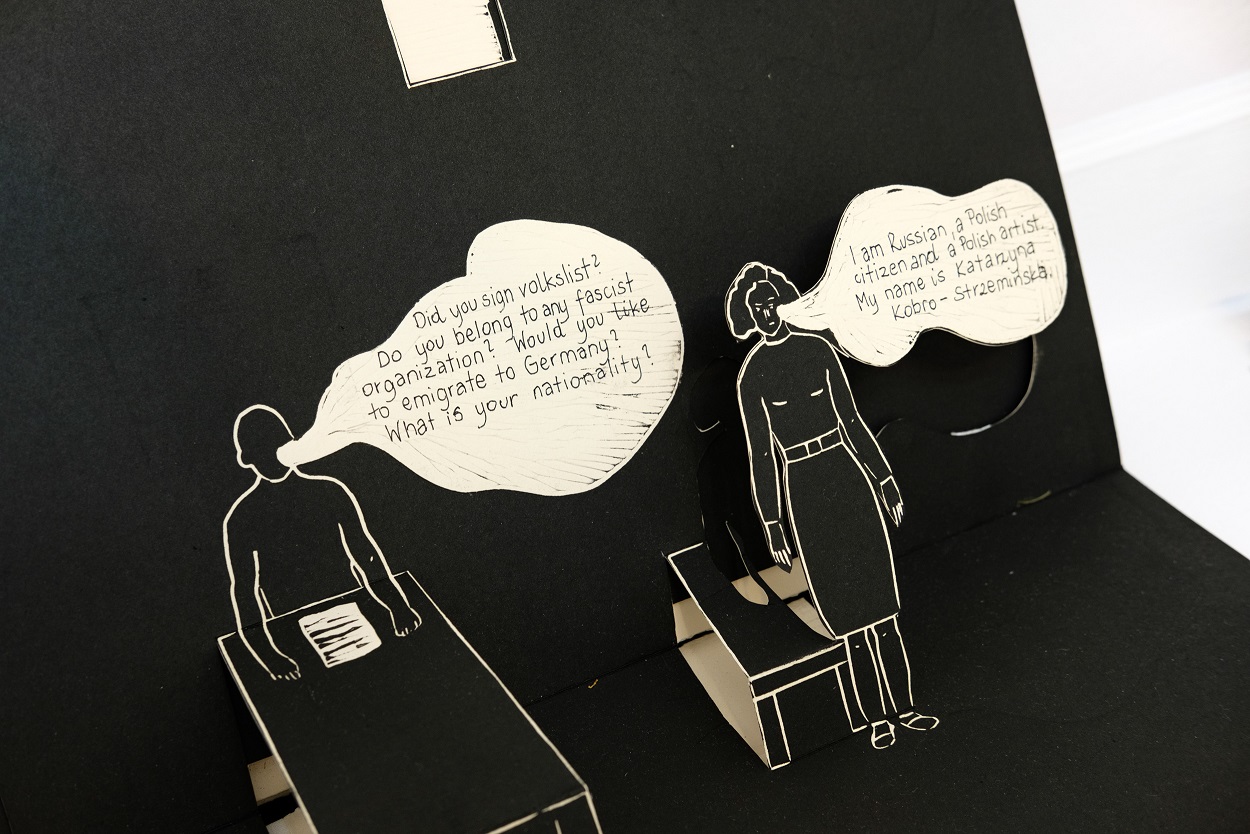

Niespodziewana opowiada poprzez sceny, które są syntezą danego etapu życia interesującej ją artystki. Nie obawia się mitologizacji życia Kobro, raczej prowadzi z tym zjawiskiem grę. Formuła książek dla dzieci z ruchomymi scenkami, pozwala jej na zderzenie naiwnej, ciepłej formy z przygnębiającymi treściami. Stosuje także pudełeczka z wyciętymi rysunkami ustawione w przestrzenną kompozycję oraz komiks. W ten sposób udaje jej się uniknąć patosu i rozpaczy, jest empatyczna wobec swoich bohaterek, lecz jednocześnie – rzeczowa. Kontynuując pracę wzmacniania pamięci, zrekonstruowała strój Kobro: dwie suknie widoczne na ocalałych zdjęciach, szal i czapeczkę. Długo uważano, że ubiory te zostały zaprojektowane przez męża artystki, Władysława Strzemińskiego, gest Niespodziewanej jest ich odzyskaniem dla właściwej autorki – samej Kobro.

W 2015 roku w twórczości krakowskiej artystki pojawiła się Erna Rosenstein. W jej wypadku inspiracją stało się jedno wydarzenie. Niespodziewaną interesował przede wszystkim sposób, w jaki Rosenstein poradziła sobie z traumą po wydarzeniu, jakim było zamordowanie rodziców w jej obecności i uratowanie się przez nią cudem przed pewną śmiercią. Trudno w ogóle sobie wyobrazić taką sytuację i możliwość dania sobie z nią rady (oraz życia dalej), nie mówiąc już o tym, że morderstwo dokonane przez polskiego szmalcownika w lesie przy torach kolejowych, należy do niepoddających się obrazowaniu. A jednak Erna Rosenstein opowiadała o tej tragedii w biograficznych relacjach, podejmowała ją aluzyjnie w malarstwie i rysunkach.

Niespodziewaną interesuje przede wszystkim świat wyobraźni starszej artystki, przebijający przez jej styl obrazowania sposób radzenia sobie z traumą. W bogatej twórczości Rosenstein dominującym nastrojem była melancholia. Wskazują na to analizy zawarte w monografii artystki, autorstwa Doroty Jareckiej i Barbary Piwowarskiej. Rosenstein nieustannie powtarzała prześladujący ją motyw odciętych głów rodziców i zanikanie, blaknięcie ich wizerunków. Cykl Niespodziewanej Erna pokazuje tło całego wydarzenia, boleśnie nawiedzającego artystkę w niekończącej się repetycji. Sceneria lasu, pełnego suchych gałęzi, pajęczyn i kolców. Ten styl obrazów jakby wzięty prosto z baśni zderza się ze straszną treścią, nieco ją neutralizując i czyniąc ją możliwą do przyjęcia. Fragment wiersza Rosenstein zacytowany przez Niespodziewaną w jednym z kolaży, Gdybym była naprawdę / wycięłabym sobie serce, wskazuje na jeszcze jedną konsekwencję potworności, jaką przeżyła członkini Grupy Krakowskiej – nękające ją nierealność, poczucie nieistnienia. Odwołujący się do takich odczuć motyw braku i pustki pojawia się w kilku kompozycjach z serii Erna.

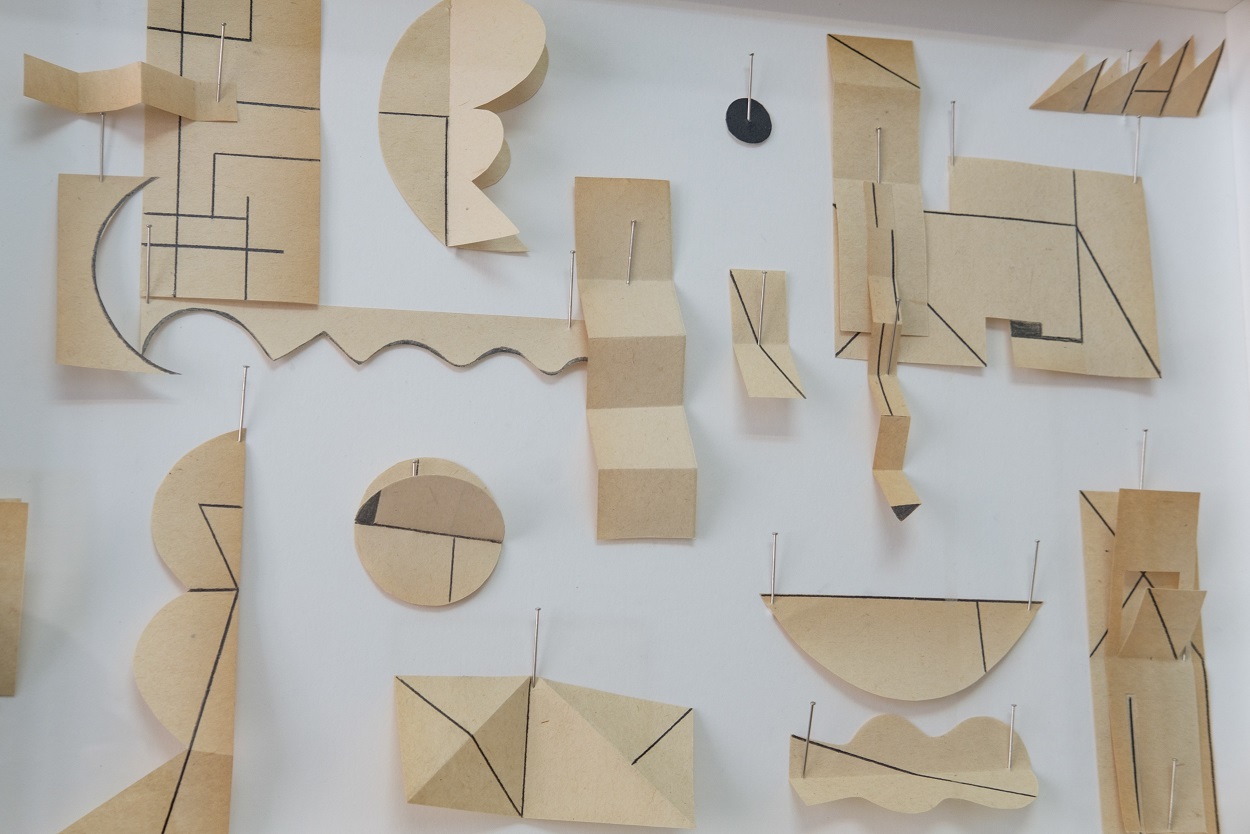

Gdy w 2018 roku Niespodziewana zwróciła się ku postaci Marii Jaremy, tym razem sięgnęła po abstrakcję. W kolażach i grafikach zastosowała własny język, bazujący na wypracowanym przez Jaremiankę. Jego podstawą stała się powtarzalność i rytm mnożących się form, które wybijały się ze stanu płaskiego w przestrzeń. Były to jakby zmiękczone formy geometryczne, które stawały się obłe, biologiczne, a ich zadaniem było stwarzanie wrażenia płynięcia w przestrzeni, drgania. Znakomicie został uchwycony tutaj styl Jaremianki, której prace dają właśnie wizję harmonijnego przepływania form, często się o nich mówi – zresztą bazując na jej sugestiach – że przedstawiają taniec. Według świadectw, które skrupulatnie przytoczyła w swojej książce Agnieszka Dauksza, Jarema nie dbała o powierzchowość i była osobą o niezwykłej charyzmie i stanowczości. Cechowała ją bezpośredniość, wytrwałość i kruchość. Była pełna przeciwieństw, czy jednak nie zespalały się w jedno w jej sztuce? Kolekcja (dla Marii) autorstwa Malwiny Niespodziewanej zawiera więcej pogody i odnosi się w sposób bardziej zawoalowany do życia artystki niż dzieła odnoszące się do Kobro i Rosenstein. Życia, które także wypełnione było tworzeniem sztuki na przekór wojnie czy powojennej biedzie, a potem śmiertelnej chorobie.

Zastanawiam się czy za ideą dzieł poświęconych innym artystkom, nie stała myśl o odwróceniu zła, jakiego doświadczyły one w swoich życiach. W pracach Niespodziewanej dostrzegam bowiem gest ponadpokoleniowej i biegnącej w poprzek czasu solidarności. Możliwe, że jej zamiarem było nie tyle stworzenie alternatywnej wersji historii, co ukazanie jej ciągu dalszego, by absurdowi cierpienia i nieszczęścia, jakie spadały na jej bohaterki, nadać sens. Traktując dorobek poprzedniczek jako materiał do swoich dzieł, postąpiła jak lojalna córka, która poszukuje dla swoich duchowych matek zadośćuczynienia. By pokazać, że nie cierpiały na darmo, że to, co je dotknęło, miało w dłuższej perspektywie znaczenie dla przyszłych pokoleń i dla samej sztuki.

Tekst: Magdalena Ujma

~~~

Małgorzata Malwina Niespodziewana

Katarzyna, Erna, Maria

The artist active in the contemporary era draws inspiration from her female predecessors. She does not conceal it, quite the opposite – she openly signalises this fact in each of her pieces devoted to them. The stories and artworks of Katarzyna Kobro, Erna Rosenstein and Maria Jarema inform the works from the cycles The History about Katarzyna, Erna, Collection (for Maria). Each of these figures was an avant-garde woman artist living in the 20th century, and the stories of their lives were marked by the most horrific events: wars and their consequences, death of their loved ones, destitution and displacement. Such bad times were surely not conducive to creative work. And yet, these artists adhered to art and returned to it even at the worst of moments. Art as therapy? Not at all. The stake was to salvage something far greater. What is more, after their death, the practice of each of these artists waited for a long time for a new interpretation, a new perspective, since it had been confined to platitudes and established ways of understanding.

The artist who has introduced the work of her predecessors into today’s art circulation is Małgorzata Malwina Niespodziewana. In their attitudes she mainly discerns sensitivity, but also a vital force maintained despite the suffering caused by the external world, and – as I have already mentioned – their essential belief in art as the humanity’s salvation at liminal moments. The artistic biographies of the women artists in question feature the following sequence of events: after their initial successes comes the war with all its evil, which leaves its imprint on everything and everybody. The later times bring no redemption, nothing is what it used to be and one needs to carry on living with the burden of memory.

The way in which Niespodziewana recounts the attitudes of her protagonists involves a gesture of contrariness to high-brow Modernist styles of speaking about artists, which deemed discussing art through the prism of biographies unthinkable as it was associated with “gossip”. A developed biographic current does indeed exist in our culture, enjoying its own rights and employing storyline schemas. However, Niespodziewana’s pieces transfer this tendency in a certain way into the realm of visual arts, which is not that friendly towards it.

This strategy is downright postmodern as it is founded on the conviction that we will no longer invent anything new and all we can do is to mix existing symbols forming ever- newer constellations. Niespodziewana accepts the fact that she is standing on the shoulders of giantesses. Her predecessors developed the language of modernity, which she – their follower – can only use today, nothing more. Yet, the phenomenon of exhaustion does not necessarily mean weakness. Restoring the living memory of the antecedents is also organic work indeed: it consists in establishing a women’s version of art history – herstory – and weaving the threads of matriarchal artistic genealogy. It also involves building the artist’s own safe haven, where no one can question her activity. Niespodziewana’s gesture is therefore tantamount to building a community of women artists: acknowledgement of mothers-patronesses-avant-garde artists, but also support for sisters-colleagues who create art today.

Niespodziewana’s choice to address the oeuvre of the avant-garde pioneers coincided with an increased interest in the role and place of women artists in the field of art. At least since the beginning of the 1990s, they have been emerging from obscurity to which they were relegated by art history, and the process of strengthening the position of creative women goes on, the obstacles notwithstanding. Works by Małgorzata Malwina Niespodziewana form part of the changes occurring in front of our eyes and offer evidence that the oeuvre of the women avant-garde pioneers can be read with interest also today. This manner of reading obviously differs from the past approaches, as it is necessary to address the context of creative practice: its biographical and historical background, and to employ interpretative eclecticism developed by oneself. Malwina Niespodziewana therefore relies on biographical knowledge, but also narrative schemas used in her accounts of the stories of women artists’ lives. She deliberately taps into the resources of popular culture, evoking such genres as comic and children’s books. She recreates the emotional aura of biographical episodes, creating something of inner portraits and making a masterful use of the language of form. With regard to Kobro, she recounts the stages of her life that came to a miserable end. As for Rosenstein, she concentrates on the aura of her imaginary world. In reference to Jarema, she turns to material and form as a prism through which to highlight the elegance and fragility of avant-garde art created against the obstacles posed by the times in which the artist lived.

In 2008, Niespodziewana evoked the figure of Katarzyna Kobro. It was not the innovative artistic oeuvre of the sculptress, however, that interested her the most. Her oeuvre, which positions her among the masters and mistresses of the first avant-garde, was juxtaposed with the dramatic story of Kobro’s life. In her works devoted to the sculptress, Niespodziewana reversed the usual manner of recounting biographies. Kobro’s fate does not serve as a justification for her creative work, quite the opposite – her art was created against the circumstances of her life. Niespodziewana deliberately adopted the account of the artist’s daughter as the basis of her project, even though Nika Strzemińska was accused of lack of objectivity. Let us remember, however, that Kobro, who until the 1990s had remained known only to a narrow circle of experts, gained posthumous recognition primarily owing to the efforts of her daughter, supported by the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. Niespodziewana tapped into those achievements, while conducting her own research at the same time. Nika’s account offered her an excellent basis on which to weave her story, since the topic of The History about Katarzyna is the relation between the artist-mother and her daughter, who sought to preserve the memory of her mother. It is the history about Katarzyna as seen through Nika’s eyes.

Niespodziewana develops her story through individual scenes, which offer a synthetic vision of a given stage of Kobro’s life. She does not feel apprehensive about the mythologisation of the artist’s life, but rather plays a game with this phenomenon. The choice of the children’s picture book format with pop-up scenes allows her to juxtapose the naive and warm form with depressing content. She also uses boxes with cut out drawings arranged to form a spatial composition as well as comic strips. The artist thus succeeds in avoiding pathos and distress, she empathises with her protagonists, while remaining factual at the same time. Continuing her efforts towards reviving memory, she reconstructed Kobro’s attire: two dresses visible in preserved photographs, a shawl and a cap. It was believed for a long time that those garments had been designed by the artist’s husband, Władysław Strzemiński, and therefore Niespodziewana’s gesture reclaimed them for Kobro as their actual designer.

Erna Rosenstein appeared in the work of the Krakow artist in 2015. In this case, inspiration came from a single event. Niespodziewana took particular interest in how Rosenstein had coped with the trauma caused by the murder of her parents, which she herself had witnessed, and her own miraculous rescue from certain death. It is hard to even imagine such a situation and the possibility of coming to terms with it (and carrying on living), not to mention the fact that the murder perpetrated by a Polish shmaltsovnik (person who blackmailed Jews in hiding – trans. note) in a forest near railway tracks is something that escapes representation. And yet, Erna Rosenstein recounted that tragedy in biographic accounts and alluded to it in her paintings and drawings.

Niespodziewana mainly takes interest in the world of the elderly artist’s imagination and her ways of coping with trauma that transpires from her visual style. The prevailing mood in Rosenstein’s abundant oeuvre is melancholia, as shown by the analyses featured in the artist’s monograph authored by Dorota Jarecka and Barbara Piwowarska. Rosenstein constantly repeated the haunting motif of her parents’ decapitated heads and the gradual disappearance, the fading of their images. Niespodziewana’s cycle titled Erna depicts the background of the entire event that painfully haunted the artist in an endless repetition – a forest scenery that abounds in dry branches, spiderwebs and thorns. This style of painting, as if straight from a fairy tale, collides with the horrific content, neutralising it slightly and making it possible to digest. A fragment of Rosenstein’s poem quoted by Niespodziewana in one of her collages: “If I was for real, I would cut my heart out”, indicates yet another consequence of the atrocity experienced by the Krakow Group member: the sense of unreality and non-existence that gnawed at her. The motif of lack and void, which bears reference to such feelings, appears in several compositions from the cycle Erna.

When in 2018 Niespodziewana turned her attention to the figure of Maria Jarema, she focussed on abstraction. Her collages and graphic prints rely on her own artistic language based on the one developed by Jarema. Serving as its foundation is the repetitiveness and rhythm of multiplied forms that emerge from flatness and into the spatial dimension. Those are akin to softened geometrical forms that become rounded, biological, and their task is to generate the impression of floating in space, vibration. Niespodziewana managed to perfectly capture the style of Jarema, whose works produce the vision of harmoniously flowing forms and are often said – according to the artist’s own suggestions – to represent dance. Testimonies diligently quoted by Agnieszka Dauksza in her book reveal that Jarema did not care about appearance and was an extraordinarily charismatic and resolute person. Her characteristic features included straightforwardness, persistence and fragility. She was full of contradictions, but did they not in fact unify in her art to become one? Collection (for Maria) by Niespodziewana is more cheerful and refers in a more veiled way to the artist’s life than her works devoted to Kobro and Rosenstein. A life that was also filled with artmaking against the obstacles of the war and post-war destitution, followed later by her terminal illness.

I am wondering whether the idea of pieces devoted to other women artists is not informed by the thought of reversing the evil which they experienced in their own lives. This is because in Niespodziewana’s works I discern a gesture of intergenerational solidarity that runs across time. Perhaps her intention is not to create an alternative version of history, but to depict its continuation in order to give meaning to the absurd suffering and misery that befell her protagonists. Treating the oeuvre of her predecessors as the material for her own works, she acts like a loyal daughter, who seeks redress for the wrongs experienced by her spiritual mothers. She does that in order to show that they did not suffer in vain and that their experience proved to be significant in the longer run for the future generations and for art as such.

Text: Magdalena Ujma