Wystawa indywidualna w lokalu_30: Tim Beckenham (Wlk. Brytania), malarstwo

Wystawa zbiorowa w Galerii XX1: Tim Beckenham, Thomas Hauri, Zuzanna Janin, Szymon Kobylarz, Karolina Zdunek

Kuratorka: Agnieszka Rayzacher

W 1919 roku młody Ludvig Mies van der Rohe stworzył pierwszy szkic dwudziestopiętrowego, szklanego wieżowca. Ten nigdy nie zrealizowany fantastyczny projekt dał początek architekturze „skóry i kości”. Określenie „skin and bones” zostało ukute przez samego Miesa i miało charakteryzować budynki, których trzon konstrukcyjny stanowiły stal oraz beton, otoczone powłoką ze szkła. Przez kilkadziesiąt lat van der Rohe projektował budynki o znacznie mniejszej skali – swoją ideę mógł w pełni zrealizować dopiero w latach 50. w Stanach Zjednoczonych, jako uznany architekt i profesor Illinois Institute of Technology. Wpływu jego koncepcji na współczesną architekturę nie sposób przecenić. Najlepszym dowodem zdają się być centra współczesnych metropolii. To prawda – ideały twórców modernizmu zostały zaadaptowane do potrzeb kapitalistycznej gospodarki, architekt-wizjoner stał się architektem-wykonawcą, a w miejsce Zeitgeist i Gesamtkunstwerk wszedł zwykły pragmatyzm. Wciąż jednak prostota form, abstrakcyjność, puryzm modernizmu zdają się inspirować nie tylko kolejne pokolenia architektów, ale również artystów.

Brytyjski malarz Tim Beckenham urodził się w latach 70. Londynie. Dzieciństwo spędził w dzielnicy typowych szeregowych domów stawianych w epoce gospodarczego boomu epoki wiktoriańskiej. Jako student Wimbledon School of Art zaczął fascynować się architekturą późnego modernizmu. Początkowo bohaterami jego prac na papierze były bloki mieszkalne – efekty powojennej polityki mieszkaniowej rządu Wielkiej Brytanii. Ich architektura – nie lubiana przez większość Brytyjczyków, nagle okazała się uwodzić bliskimi estetyce high-tech prostotą i minimalizmem. Po blokach nadeszły budynki biurowe – zbudowane według zasady „skin and bones”, wyabstrahowane z miejskiego otoczenia, osadzone w szarym, neutralnym tle dostojne i oficjalne, bez śladów ludzkiej obecności. Towarzyszą rzeźby umieszczane latach 60. przed głównymi wejściami do biurowców. Ich amorficzne kształty w zestawieniu z surowością budynków i szarym tłem podkreślają nadrealny charakter przedstawień. Najnowsze prace Beckenhama to rodzaj malarskich szkiców fantastycznych struktur, mających więcej wspólnego z rzeczywistością wirtualną lub projektami 3D niż z realną architekturą.

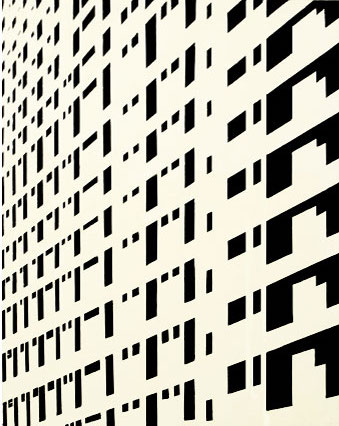

Płaskości obrazu przeciwstawia się również Karolina Zdunek. Z fascynacji wczesnym modernizmem powstała seria „Bloków”. Zaczerpnięty z codzienności wzór, stał się pretekstem dla czysto malarskich rozważań. Blok, ikona PRL-u, modernistyczny ideał zbanalizowany i sprowadzony do miana zdehumanizowanej mieszkaniowej masówki, w interpretacji Karoliny zyskał swoje pierwotne piękno. Powierzchnię elewacji artystka sprowadziła do siatki rastra lub poziomych linii – regularnej struktury geometrycznych kształtów widzianych w perspektywicznym skrócie. Miejska szpetota została zastąpiona czystą formą, pozbawioną śladów ingerencji i bytności człowieka.

W opozycji do tych wyidealizowanych przestrzeni stoją prace studenta V roku malarstwa katowickiej ASP, Szymona Kobylarza. Jego kartonowe modele przywodzą na myśl popadające w ruinę budynki przemysłowe – betonowych świadków gospodarczej prosperity regionu. Artysta nie rekonstruuje jednak konkretnych obiektów, ale tworzy swoje własne, inspirowane sumą doświadczeń mieszkańca Śląska. Każdy z kartonowych modeli jest poddawany działaniu ognia i wody, a prowokowane „katastrofy” są rejestrowane przez kamerę video. Pozostałością po tym działaniu są szkielety konstrukcyjne, nieco sarkastyczny komentarz do architektonicznego ideału „skin and bones” Miesa van der Rohe.

Z kolei tworzywem zwiewnych „Pokrowców” Zuzanny Janin jest biały jedwab. „Pokrowce” stanowiąc metaforę prywatnej przestrzeni, są jednocześnie odniesieniem do modernistycznego ideału oraz socjalistycznej praktyki. Kryją również nadzieję na uchronienie anektowanych symbolicznie przestrzeni przed niknięciem czeluściach niepamięci. Tak, jak pozostałe prace z tego cyklu, prezentowany na wystawie pokrowiec „Little” niesie za sobą prywatną historię artystki. Powstał na początku lat 90., kiedy Zuzanna Janin mieszkała w typowym ursynowskim bloku, a jej życiową przestrzeń (tak jak i przestrzeń tysięcy sąsiadów) stanowił kubik z prefabrykowanych betonowych płyt. Jedwabny pokrowiec o wymiarach typowego segmentu stanowi również metaforę bardziej ogólną, odnoszącą się do życia pewnej zbiorowości zamkniętej w szufladach masowego budownictwa mieszkaniowego, do ogólnopaństwowych planów oraz styku szczytnych idei z rzeczywistością.

Architekturę uwikłaną w ideologię i historię przedstawia również szwajcarski artysta Thomas Hauri. Jego niemal niewidoczne wielkoformatowe akwarele z serii „Prora” powstały po wizycie artysty na niemieckiej wyspie Rügen. Tu w latach 1936-39 naziści wybudowali ciągnący się prawie 5 km nadmorski dom wczasowy, który miał służyć jako miejsce zbiorowego i kontrolowanego wypoczynku niemieckich robotników (idea jako żywo przypominająca PRL-owski FWP). Budynki te nigdy nie spełniały przeznaczonych im funkcji – w czasach NRD wykorzystywane były częściowo przez wojsko, reszta kolosa popadała w ruinę. Co zaskakujące architektura kompleksu Prora stanowi zwulgaryzowaną formę modernizmu, z niewiadomych przyczyn zaakceptowaną przez nazistowskich zleceniodawców. W interpretacji Thomasa Hauri kolos z wyspy Rügen to zanikające poziome pasy betonowych konstrukcji, równie nierealne i zagadkowe, jak nieodgadniony jest rzeczywisty zamiar jego konstruktorów.

~~~~~

SKIN AND BONES

Tim Beckenham (GB), Thomas Hauri (CH), Zuzanna Janin, Szymon Kobylarz, Maciej Kurak, Karolina Zdunek

curator: Agnieszka Rayzacher

XX1 Gallery, Warszawa, Poland

5.01 – 27.01.2007

Kameralna Gallery, Słupsk, Poland

24.01 – 28.02.2008

n 1919 young Ludvig Mies van der Rohe created the first sketch of a 20-storey glass skyscraper. That design, which was never realized, was the beginning of „skin and bones” architecture. The name was created by Mies himself and was to characterize buildings whose shell consisted of steal and concrete surrounded by a layer of glass For several decades van der Rohe designed buildings in a much smaller scale, it was not before the late forties that he was able to put his ideas into reality in the United States, as a recognised architect and professor of Illinois Institute of Technology. It is difficult to overestimate the influence and significance of his work for contemporary architecture and visual arts.

The exhibition „Skin and Bones” is an attempt to show modernistic architecture as a source of inspiration for contemporary artists. Participating in the project are artists from Poland, Great Britain and Switzerland, which makes it possible to confront different experiences, interpretations and visions of modernism.

A British painter Tim Beckenham was born in the seventies in London. His childhood he spent in a district of terraced houses built in industrial boom of Victorian times. As a student of Wimbledon School of Art he became fascinated with late modernism architecture. At first his objects on the paper were blocks of flats – results of postwar housing policy of the British government. Their architecture – disliked by most Britons, suddenly appeared to seduce with close to high-tech simplicity and minimalism. After being fascinated with blocks Beckenham started presenting office buildings – created according to the „skin and bones” principle, eliminated from urban surrounding, placed in a gray neutral background, dignified and official, with no traces of human presence. They are accompanied by sculptures which used to be placed in front of the main entrances to office buildings. Their amorphous shapes in combination with roughness of the buildings and gray background emphasize the surrealistic character of presentations. The latest works of Beckham are a kind of painting sketches of fantastic structures, which have more in common with virtual reality or CD projects than with real architecture.

The series „Blocks” by a Warsaw painter Karolina Zdunek was also inspired by modernism. The pattern taken from everyday life became a pretext for purely painting considerations. The block, which was an answer to social architecture, trivialized and brought to be a dehumanized housing substance, in Karolina’s interpretation regained its original utopian beauty. The artist reduces the texture of elevations to a raster net or horizontal lines – a structure of geometric shapes seen in foreshortening . The urban banality is replaced by ” pure form”, deprived of any signs of human interference or presence.

In contrast to these idealized images of architecture are works of Szymon Kobylarz, a graduate of Academy of Fine Arts in Katowice. His cardboard models bring to mind the industrial buildings that fall into ruin – concrete witnesses of the region’s economic prosperity. However, the artist does not reconstruct particular objects, instead he creates his own, being inspired by a sum of experiences of an inhabitant of Silesia. Each of the models is exposed to the fire and water, and the „disasters „provoked in this way are recorded by a video camera. The cardboard structural skeletons are remains of these actions, a bit sarcastic commentary to the architectural „skin and bones” ideal.

White silk is material of Zuzanna Janin’s „Covers”. Being a metaphor of private space they at the same time refer to the modernistic ideal and the practice of PRL. They are also a hope for protection of the symbolically annexed spaces from disappearing in abyss of oblivion. Similarly to other exhibited works, the cover „Little” brings some private history of the artist. It was created in the early nineties when Zuzanna used to live in a typical block of flats and her living space (like thousands of her neighbours’) was a cube of prefabricated concrete slabs. A silk cover of a size of typical unit is an attempt of „timing” the concrete reality and a metaphor of the clash social utopias’ clash with reality of life.

A project of Maciej Kurak was also created on one of the most popular Polish prefab block housing estates. The artist decided to build a miniature of a block at Puszczyka Street 20 in Warsaw Ursynów district. The miniature in a scale 1:6 was an exact copy of the original and was placed on the lawn in its neighbourhood. Inside there was a bedsitter, completely furnished and of natural size. A trip to find the place of installation itself was a part of Maciej Kurak’s work – the topography of Ursynów, like many other prefab block housing estates, is a proof how impractical is a typical way of addressing „a street and number” in the case of estates designed as concentrations of detached blocks. At the same time however, wandering along alleys among subsequent blocks, which appeared not to be the one searched for , it was difficult not to confirm that this bathed in the green place ,designed just for people, not for money, is simply beautiful. Thus Kurak’s work is a specific commentary to the criticism faced by architecture and town-planning of soc-modernistic estates. With his project the artist came into the local community that identifies with its place and looks after its aesthetics, far away both from automation of life and „block pathology”. On the exhibition the work of Kurak is presented in a form of documentary – a „sequence of frames” animation.

Thomas Hauri, a Swiss artist, realizes his fascination with architecture of modernism in water paints and photography. While roving European towns, both western European and those that used to belong to Soviet Block countries, the artist „collects” modernistic buildings, dating from the early modernism period, those from the sixties or seventies and also contemporary neo-modernistic realizations. He focuses on monumental industrial buildings, office buildings and ordinary blocks of flats as well. The results are big-sized paintings and A4 sized collages. These charming urban notes are the effect of being enchanted with aesthetics of modernism, and a specific proof for universalism of its architectural language.