“Robakowski’s work is stubbornly autonomic. For decades it remained resistant to dominant trends, preferring cognitive and expressive function to surrendering to current events of artistic life, but becoming, at the same time, its important creative element.”

Józef Robakowski, born in 1939 in Poznan, dedicated all his artistic activity to the inquiry of the nature of film. The artist chose to spend most of his life in Lódz, the city where the circle of Polish pre-war artistic avant-garde once flourished, where the Muzeum Sztuki, first museum of modern art in Poland was established, where the National Film School educated dozens of prominent Polish film artists, including Roman Polanski and Andrzej Wajda.

Robakowski’s experiments on the nature of film tape, on the very conjunction of image and sound, characteristic to that medium, make his work a sort of a follow-up of the grand artistic experiment led by 20th Century avant-garde currents, before it was interrupted by the outburst of WW2. Since late 1950’s Robakowski, in parallel with artistic phenomena seen in Western Europe and in the USA, was exploring the very borders of film and definitely extending them.

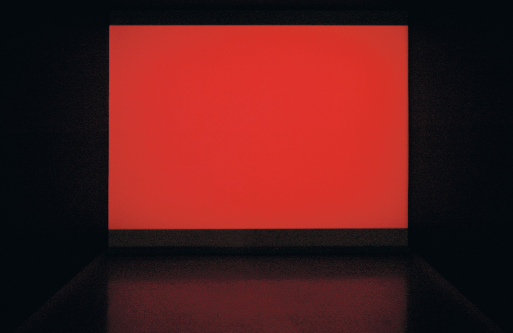

Tautological nature of his works is evident in his TEST 1 and TEST 2 from 1971, presented in the exhibition in lokal_30_warszawa_london. This is a screening of a film test, the aim of which was to reach better understanding and insight into the very essence of film projection through deconstruction of the fundamental constitutive elements of that medium.

“Every thing has its full potential hidden deep, but present already at an embryonic stage. This is the essence. Any noble and open-minded soul is going to bring things to perfection, to assist things in realizing that essence, fulfilling that potential. This is love; perfect love of a beloved object.”

Robakowski, as surrealists before him, was not satisfied with traditional scope of technical possibilities the film projection offered. He decided to show a specific nature of film tape and of the source of light as such, rather than as just tools or materials. To that purpose he irregularly perforated the tape so that a flash of pure and direct projector light, not compromised by any sort of filter, beacons at the viewer between intervals of darkness. The blinding stream of light hits the eye, disturbing the viewer’s feeling of comfort and safety, typical to dark cinema room, as described by Umberto Eco.

The principal motive of TEST 1 and TEST 2 is the light flashing in darkness. The play of light and darkness suggests, of course, symbolic meanings of both, rooted so deeply in European culture (no need to mention any more than Ancient aletheia, the beginning of the Christian Bible or Les Lumières).

Evocation of power of the light, conceiving the light as energy is present not only in Robakowski’s films, but in his philosophy, in the way he understands and describes art, as well:

“I am interested in “pure screen”. My TEST – the film from 1971 – being the simplest emission of light upon a screen, reveals that power. In psychological terms it works excellently. Actually, it works till it hurts, as cinema projection is about really strong beam of light, about an energetic force which computer screen doesn’t have at all. Cinema is the power of light, the very magic of it.”

A second film Attention: Light! screened in a separate room of the gallery, made over 30 year later and lending its title to that of the entire exhibition, is the effect of friendship between Robakowski and Paul Sharits.

The film, made in cooperation with Wieslaw Michalak, is dedicated to memory of the American structuralist, with whom Robakowski collaborated at the turn of 1970/1980’s. In 1981 Sharits sent to Robakowski the sheet of a film score, suggesting him to use it to shoot a film. The project remained incomplete due to the Martial Law that soon followed in Poland. Eventually, the film was made in 2004. Sharits based its structure upon close synchronicity between musical and visual layers. The film is an effect of extremely rigorous, constructivist formal procedure that subordinated specific visual values to melodic line of a musical piece. During the screening subsequent tones of Frederic Chopin’s Mazurka op. 68 nr. 4 are accompanied on the screen by eight corresponding colours. The vibration of changing colours and emanation of light compose into a coherent composition with that nostalgic piece of piano music. Spots of colour, pulsating to the rhythm of music, combine revocations to structural cinema of the American artist with Robakowski’s emphasis upon vital energy of colour and light.

The choice of works shown, made by Józef Robakowski together with curators of lokal_30_WL is meant to present to British audience the role and particular place of the Artist in history of European art and to highlight close artistic relations between movements evolving in Western and Central Europe.

Michal Suchora