WARSAW GALLERY WEEKEND 2016

FILIP BERENDT, EWA JUSZKIEWICZ, KATYA SHADKOVSKA

Syndrom Gauguina

Syndrom Gauguina to prezentacja trójki artystów – Filipa Berendta, Ewy Juszkiewicz i Katyi Shadkovskiej. Są to trzy wystawy indywidualne, które łączy wątek antropologiczny oraz temat przemiany – jej potrzeby, niemożności lub chwili, gdy następuje.

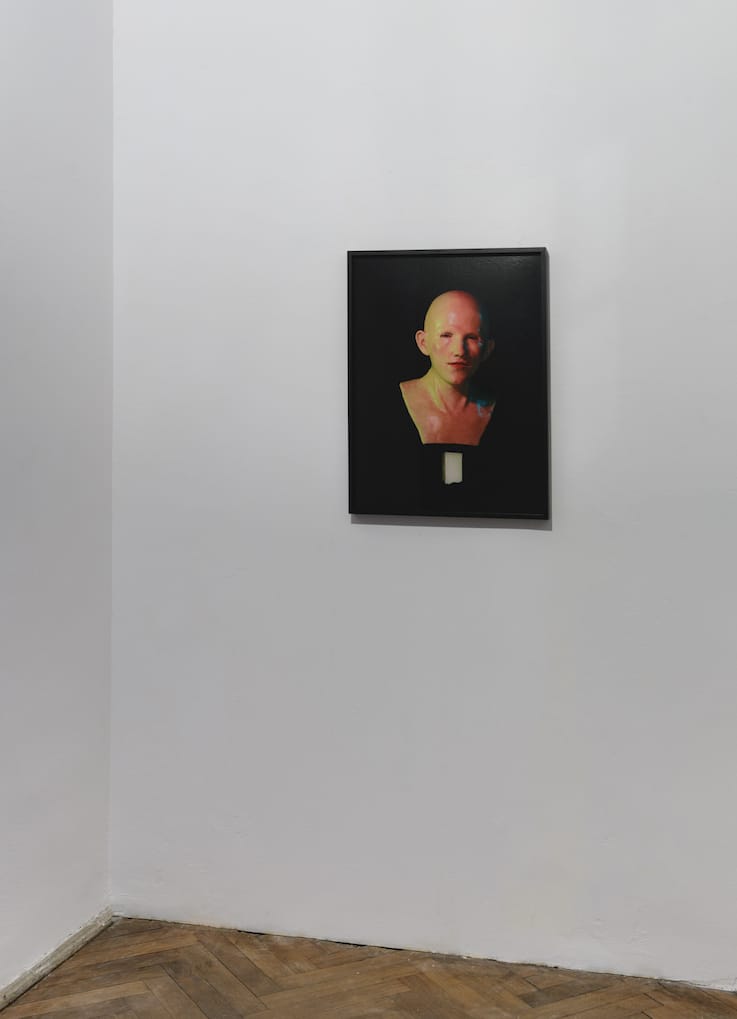

Filip Berendt jest fotografem, rzeźbiarzem i autorem obiektów. Każde z jego zdjęć poprzedza tworzenie obiektu, który następnie fotografuje. Monomit to projekt łączący autorską fotografię z abstrakcyjnym malarstwem – uwiecznione obiekty to przestrzenne kolaże powstałe na ścianie pracowni Berendta, zniszczone po sfotografowaniu. Podobna metoda towarzyszyła Berendtowi już w paru poprzednich cyklach (Every Single Crash, Pandemia), gdzie jedynym fizycznym śladem po stworzonych pracach – a zarazem ostatecznym efektem procesu twórczego – była fotografia. Najnowsze prace Berendta odwołują się do monomitu, terminu wprowadzonego przez amerykańskiego mitoznawcę Josepha Campbella (samo wyrażenie zostało zapożyczone od Jamesa Joyce’a). Monomit określa rozpoznany przez Campbella archetypiczny wzorzec struktury fabularnej wspólny dla mitycznych opowieści, przejawiający się poprzez motyw podróży bohatera, będącego nośnikiem uniwersalnych prawd o osobistym samoodkryciu i samotranscendencji, o rolach w społeczeństwie i w relacjach. Bohater, według Campbella, a za nim Berendta, to człowiek, który wyrusza w drogę prowadzącą go do celu, jakim ma być ostateczna głęboka duchowa przemiana. Podróż bohatera to nadawanie życiu sensu, poszukiwanie i odkrywanie go na kolejnych jej etapach.

Ewa Juszkiewicz jest autorką obrazów, rysunków, kolaży oraz rzeźb. Charakterystyczną cechą wielu jej prac jest inspiracja portretem, przede wszystkim portretem kobiecym. Artystka reinterpretuje, a zarazem niszczy i tworzy na nowo znane z historii sztuki wizerunki kobiet – bazuje na klasycznych dziełach malarskich, dokonuje ich przetworzenia, odbiera im oczywistość i znany nam porządek. W twórczości Juszkiewicz bardzo istotny jest również motyw maski. Ta swoista maskarada, którą uprawia artystka, służy podważeniu statusu i funkcji dawnego portretu i zbudowaniu na tej „ruinie” nowego wizerunku, czy raczej kolekcji wizerunków. Nowy cykl Juszkiewicz jest oparty na archiwalnych fotografiach dzieł sztuki, które zostały uznane za zaginione, skradzione lub zniszczone w czasie pożaru czy podczas wojny. Napięcie między destrukcją a tworzeniem powraca tu ze zdwojoną siłą. Ponieważ kultura opiera się dziedzictwie przeszłości, często z trudem przychodzi nam zaakceptowanie faktu zastępowania tego, co stare, nowym, choć przez cały czas jesteśmy tego świadkami – urbanistyka i architektura od wieków żywią się ruinami. Akt niedosłownego, bo reinterpretującego odtworzenia zniszczonego lub zaginionego dzieła obrazuje napięcie między nostalgiczną walką z zapomnieniem, a potrzebą zmian i dążeniem do nowego. Artystka mówi, że dobór prac-pierwowzorów nie był przypadkowy. W trakcie przygotowań spośród wielu zdjęć, które oglądała, wybrała obiekty będące ilustracją jej własnych wspomnień dotyczących zmian i życiowych zwrotów. Czasem przedstawienie ilustruje jakieś wyjątkowo mocne wspomnienie, innym razem to luźne skojarzenie, przywołanie pewnej szczególnej aury. Utracone dzieła i tęsknota za nimi splotła się więc z rodzajem „kontrolowanej nostalgii” powodowanej osobistymi przeżyciami artystki, które są tajemnicą skrywaną, a zarazem ujawnianą przed odbiorcą.

Katya Shadkovska zajmuje się przede wszystkim wideo, jest również aktywna jako kuratorka i animatorka kultury. Działa pomiędzy Polską a Rosją, współpracując z niezależnymi rosyjskimi środowiskami artystycznymi. Film, który prezentujemy jest owocem jej aktywności w Rosji. Artystka poprzez historię młodego transseksualisty sięga do stereotypów męskości i zmian, jakim ulegają one aktualnie. Bohaterka Shadkovskiej, Julia, mieszka samotnie na jednym z blokowisk Petersburga i utrzymuje się z prostytucji. Zmaga się z brakiem akceptacji, jest bita, poniżana, a jednak nie zamierza rezygnować ze swojego sposobu życia. Beznamiętna opowieść Julii koncentruje się na codzienności, choć w istocie jest dramatycznym wyznaniem obcego, osoby, która nigdzie nie przynależy, która nie może się odnaleźć w żadnym środowisku, nawet osób myślących tak jak ona. Sama artystka tak mówi o niej: Sporo osób homo i transseksualnych emigruje teraz z Rosji. Znalazłam dla Julii prawników, którzy załatwiają wszystkie papiery, formalności i dogadują się z krajem zachodnim, który jest gotów udzielić takiej osobie azylu. Julia bardzo mi dziękowała. A potem zniknęła. Na pytanie dlaczego, odpowiedziała: „Ale co ja mam robić na Zachodzie? No i w ogóle…podoba mi się tu”.

////////

„Syndrom Gauguina“ to trzy wystawy i trzy opowieści.

Łączące w sobie malarstwo i fotografię prace Berendta obrazują monomit – figurę antropologiczną stworzoną przez amerykańskiego mitoznawcę Josepha Campbella. Przytoczona historia oparta jest na faktach i może stanowić współczesną wersję mitologicznej wyprawy bohatera.

W 1994 roku dwóch przyjaciół, Adam i Rafał, postanowiło zsunąć się do opuszczonej kopalni, 20 metrów w dół. Rafał kończył właśnie geologię, pisał pracę magisterską. Chciał zanurzyć się we wnętrzu Ziemi. Nie wiedział, że zmieni to jego życie. Kiedy postanowili wrócić na powierzchnię, okazało się, że pojedyncza lina, którą mieli, jest za śliska. Szybko zdali sobie sprawę z tego, że kolejne próby wspinaczki będą tylko stratą energii. Niewielki prowiant zjedli od razu, bateria w latarce wyczerpała się błyskawicznie. Mieli świece i lampę naftową, ale wkrótce zabrakło zapałek. Leżeli skuleni na żwirowym podłożu. Strasznie bolało. Pili wodę z kałuży i własny mocz. Szybko zaczęli mieć wizje – wydawało im się, że przechodzą przez skały, w kompletnych ciemnościach widzą zachód słońca. Spotkali też Królową Ziemi – w długiej szacie i koronie na głowie. Okazało się, że każdy z nich miał podobne przeżycia. O większości opowiedzieli sobie po wyjściu – kiedy po 24 dniach skrajnie wykończonych mężczyzn odnalazła ekipa ratunkowa. Nic już nie było takie, jak wcześniej.

Ewa Juszkiewicz swoje najnowsze obrazy maluje na podstawie zdjęć archiwalnych dzieł utraconych. Przytoczona przez nią opowieść dotyczy historii jednej z prac.

Wraz z nastaniem reżimu nazistowskiego życie żydowskiej rodziny przedsiębiorców Hessów uległo drastycznej zmianie. Thekla, wdowa po Alfredzie, została sama z synem Hansem, który miał przejąć pieczę nad rodzinną kolekcją sztuki. Gdy w 1933 roku stracił pracę w domu wydawniczym Ullstein, był jednak zmuszony do wyjazdu. Przeniósł się do Paryża, potem do Londynu. To matka, która nadal mieszkała w Rzeszy Niemieckiej, zajmowała się kolekcją. Udało jej się uratować sporą część zbioru dzięki wysyłce prac na wystawę w Kunsthalle Basel w 1933. Kunsthaus Zurich odebrał je stamtąd na swoją wystawę w 1934 roku, po jej zakończeniu dzieła sztuki przechowywano w magazynach galerii. W związku z restrykcjami celnymi Thekla mogła wywozić kolekcję za granicę tylko czasowo, na podstawie „freipassu”. W 1939 Gestapo zagroziło jej w związku z przetrzymywaniem kolekcji poza Rzeszą. Thekla nie chcąc ryzykować, poprosiła dyrektora Stowarzyszenia Artystów w Kolonii o przechowanie prac, a sama wkrótce wyemigrowała do Londynu. Kiedy w 1947 roku zwróciła się do instytucji o zwrot kolekcji dowiedziała się, że dzieła wywieziono ze zbombardowanego budynku i prawdopodobnie zaginęły. Kilka lat później udało się odzyskać kilka obrazów, nigdy jednak nie natrafiono na trop ulubionej przez Theklę tapiserii „Winobranie“ autorstwa ekspresjonisty Maxa Pechsteina.

Katya Shadkovska z kolei przygotowuje film „Julia“. O swojej bohaterce artystka opowiada:

„Do Petersburga przyjechała z jednego z krajów muzułmańskich. W dzieciństwie wiedziała, że jest dziewczynką, choć wszyscy zwracali się do niej jak do chłopca. Ojciec nie mógł dowiedzieć się, że syn był kobietą. Wiedziała tylko matka, która wkrótce umarła. Dlatego Julia najpierw chce odwiedzić ojca, a dopiero potem przystąpić do operacji zmiany płci. Julia jest ciągle bita – przez ludzi na ulicy, jakichś chłopaków i przez policję. W szpitalu też nie uzyskuje pomocy, bo „jest pedałem”. Została zmasakrowana przez policjantów, którzy nie dostali haraczu z burdelu, w którym wówczas pracowała. Burdele w Petersburgu są pod „nadzorem” policji. Julia zwróciła się o pomoc, bo chciała wyjechać z Rosji. Sporo osób homo i transseksualnych emigruje teraz z Rosji. Znalazłam dla Julii prawników, którzy zajmują się pomocą takim osobom. Załatwiają papiery, formalności, porozumiewają się z krajem zachodnim, który jest gotów udzielić azyl. Julia bardzo mi dziękowała. A potem zniknęła. Na pytanie dlaczego, odpowiedziała: „Ale co ja mam robić na Zachodzie? No i w ogóle… podoba mi się tu”.”

_____

FILIP BERENDT, EWA JUSZKIEWICZ, KATYA SHADKOVSKA

Gauguin Syndrome

Gauguin Syndrome showcases the work of three artists – Filip Berendt, Ewa Juszkiewicz and Katya Shadkovska. These are individual exhibitions with common threads running through them – anthropology and transformation, its requirements, impossibility or the very moment of change.

A photographer, sculptor and creator of objects, Filip Berendt makes objects to photograph them. Monomyth project combines authorial photography with abstract painting – photographed objects are spatial collages created on the walls of Berendt’s studio and destroyed once they have been captured on film. Berendt has used that method previously in a couple of cycles (Every Single Crash, Pandemia) in which the only physical trace of the pieces he created – and thus the final effect of the creative act – was a photograph. His latest works refer to the idea of monomyth, introduced by the American mythologist Joseph Campbell (the term was originally coined by James Joyce). Monomyth stands for the archetypal pattern typical of fictional narratives, described by Campbell, shared by all mythical stories, manifesting itself as the hero’s journey, conveying universal truths about self-discovery and self-transcendence, about social and interpersonal roles. According to Campbell – and Berendt – the hero is an individual setting out on a journey leading them to the final destination: profound spiritual transformation. The journey is tantamount to making life meaningful, to searching for and discovering its meaning at consecutive stages of the trip.

Ewa Juszkiewicz creates paintings, drawings, collages and sculptures. Her works tend to be inspired by the portrait, mostly female portrait. The artist reinterprets famous historical paintings depicting women, at once destroying and recreating them – her point of departure are classic paintings which she then changes, deleting their obvious and well-known order. Masks constitute another crucial motif in Juszkiewicz’s work. The peculiar masquerade she performs aims at impugning the status and function of the old portrait as well as constructing a new image, or a collection of images, upon its ‘ruin’. Juszkiewicz’s latest cycle is based on archival photographs of works of art considered lost, stolen, destroyed by fire or during the war. The tension between destruction and creation appears stronger than before. Culture is founded on the legacy of the past and we tend to show great reluctance to accept the fact that what is old is replaced by new things, although we witness this phenomenon on a daily basis – urbanism and architecture have fed on ruins for centuries. The act of indirect – reinterpreting reconstruction of a destroyed or lost piece highlights the tension between nostalgic struggle against oblivion and the necessity of change and striving for novelty. The artist claims that her choice of original works was by no means random. During the preparation stage she went through lots of pictures, selecting those which she found related to her own memories of the vicissitudes of life. A representation may illustrate a particularly vivid memory or it may only trigger vague associations, evoking a specific aura. Lost works of arts and the longing for them have merged with a sort of ‘controlled nostalgia’ brought about by the artist’s personal experience which remains a secret, both hidden from and revealed to the public.

Katya Shadkovska is predominantly a video artist; she is also active as a curator and organizer of cultural events. She works in Poland and Russia, collaborating with independent Russian artistic circles. The film displayed at the exhibition, entitled Julia, has been inspired by her activities in Russia. Through the story of a young transsexual person she explores stereotypes about manhood and the changes they are currently undergoing. Shadkovska’s protagonist, Julia, lives alone in a block of flats in Petersburg, earning her living as a prostitute. She struggles against lack of acceptance; she is beaten and humiliated but unwilling to give up her way of life. Julia’s unemotional story focuses on daily life, being in fact a dramatic confession of the stranger, a person that belongs nowhere and is incapable of finding her own place even among people like her. The artist describes her: Many homosexual and transsexual people are leaving Russia. I managed to find lawyers who would help Julia get all necessary documents and go through formalities; they could find a Western country that would grant asylum to her. Julia said she deeply appreciated that. And then she disappeared. When I asked her why, she replied: “What would I do in the West? Anyway… I like it here.”

////

Three exhibitions and three stories that unite in a common thread of transformation – its needs, obstacles and its achievement.

In bringing together painting and photography, Berendt’s works depict a monomyth – an anthropological figure devised by the American scholar Joseph Campbell. His story is one based on fact and figures as a contemporary narrative of the hero’s mythical journey.

W 1994 two friends Adam and Rafał descended into a deserted coalmine, 20 meters deep. Rafał was just completing a Master’s degree in Geology. He wanted to explore the centre of the earth. He had no idea how it would change his life. When they were ready to resurface, they found the single rope they had was too slick. They quickly realized any attempt at climbing it would only exhaust them. They ate their only food provisions right away and their flashlight burned out almost immediately. They had candles and a kerosene lamp, but soon ran out of matches. They curled up on the rocky ground. It was painful. They drank puddle water and their own urine. They began to have visions – they started to believe they were climbing mountains and that they could see the sun set through the darkness. They also met Mother Earth – in a long cape and a crown on her head. Each of them experienced similar visions. They didn’t share them with each other until after they’d been rescued. 24 days after they entered the cave a rescue team found the two decimated men. Nothing was ever the same for them again.

Ewa Juszkiewicz creates her paintings on the basis of archive photographs of lost works. Here she describes the story of one of the works she’s revived.

As the Nazi regime rose to power the life of the Hesses, a family of entrepreneurs, was dramatically changed. Thekla, widowed after the death of her husband Alfred, remained with her son Hans, who was to take the reigns over management of the family’s art collection. When in 1933 he lost his job at the Ullstein publishing house, he was forced to emigrate. He moved to Paris, then London. His mother remained in Germany to look after the collection. She was able to save a large part of the collection by sending a number of works to the Kunsthalle Basel in 1933. Kunsthaus Zurich took them over in 1934 for their own exhibition and then stored them in its warehouse when it was over for safekeeping. Customs restrictions meant that Thekla could send the collection abroad for only short periods of time on the basis of a “freipass”. In 1939 the Gestapo threatened her with punitive action because the collection had still not returned to the Reich. Thekla was wary and asked the director of the Cologne Art Union to hold the works and immigrated to London. When she contacted the Union in 1947 to have the collection returned, she was told that the works had been removed after the bombing of the storage facility and were probably lost. Over the next few years, she managed to recuperate several of the paintings, but she never managed to track down her favourite – a tapestry by the expressionist artist Max Pechstein, titled “Grape Gathering”.

Katya Shadkovska’s film “Julia” recounts her heroine’s story:

“She had arrived in St. Petersburg from one of the Muslim nations. When she was a child, she knew that she was a girl, even though everyone referred to her as a boy. Her father was not to find out that his son was a girl. Only her mother knew, yet she passed away. That is why Julia first wanted to visit her father before having sex reassignment surgery. She was constantly getting beaten – by people on the street, gangs of boys, the police. She couldn’t get help at the hospital because she’s ‘a fag’. She was battered by the police after getting a tip from the brothel she worked in. Brothels in St. Petersburg are under the “supervision” of police. Julia asked for help because she wanted to get out of Russia. Today there are many homosexuals and transsexual individuals are trying to emigrate from Russia. I put Julia in touch with lawyers who handle such cases. I took care of paperwork, formalities, made contact with a western nation that could provide refuge for her. Julia thanked me graciously. Then she disappeared. When I asked her why, she replied ‘What am I supposed to do in the West? And anyway… I like it here…’.”

lokal_30

Wilcza 29a/12 (V piętro / 5th floor)

Warszawa