Druga wystawa indywidualna Zuzanny Janin w lokalu_30 zestawia najnowsze rzeźby, kolaże i wideo artystki z jej wcześniejszymi pracami z lat 90. i z początku lat 2000. Wystawa zbiega się z premierą książki monograficznej o twórczości artystki z tekstami Amy Bryzgel, Magdaleny Ujmy i Agnieszki Rayzacher oraz wywiadem przeprowadzonym przez Małgorzatę Czyńską.

Późną jesienią 2014 roku Zuzanna Janin wyruszyła do Brazylii, gdzie zaczęła realizację projektu LOST BUTTERFLY. Jego kanwą stała się jedna z wielu niezwykłych historii związanych z jej biografią. Na początku lat 60. roku matka artystki, surrealistka Maria Anto, namalowała obraz dla swojej jeszcze nienarodzonej córki, portretujący ją w wieku przedszkolnym w przebraniu motylka. Trzy lata później Ryszard Stanisławski, legendarny dyrektor Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi, zaprosił młodą absolwentkę ASP do udziału w Biennale w São Paulo, gdzie był kuratorem polskiego pawilonu. Obraz nigdy nie wrócił do Polski, a w archiwach zmarłej w 2007 roku Anto odnaleziono zdjęcie jego późniejszej wersji: Zuzanna idzie na bal (z 1966 roku), obrazu namalowanego na wystawę indywidualną w Zachęcie. Ponad pół wieku po tych wydarzeniach Zuzanna Janin wyruszyła śladem zaginionej pracy i po dwóch podróżach do Brazylii odnalazła u znanego tu kolekcjonera sztuki współczesnej inny obraz matki, zakupiony w latach 60. bezpośrednio na Biennale. Zuzanna Janin przyzwyczaiła nas do procesualnego charakteru swoich podróżniczych prac – tak jest i w przypadku tego projektu, na który składa się cykl wideo oraz rzeźby. Na pierwszą odsłonę projektu w Galerii Labirynt powstały dwie części filmu oraz seria rzeźb, w której dominują: uformowane z mosiężnego drutu motyle skrzydła i rzeźba LOST BUTTERFLY. Dziewczynka z cebulą i skrzydłami (Portret Matki) — niosący ze sobą wojenną historię portret Marii Anto jako dziewczynki ocalałej z transportu do Auschwitz. Poliptyk wideo LOST BUTTERFLY to zapis poszukiwań artystki od kwerendy w archiwach Biennale w Sao Paulo aż po wizytę w domu kolekcjonera, gdzie odnajduje jeden z obrazów z cyklu pokazywanego na tym biennale. Janin opowiada w charakterystyczny dla siebie sposób: mieszając wątki, przerywając relację fragmentami innych zapisów. Monotonne przeglądanie czarno-białych zdjęć oraz pożółkłych wycinków z gazet przeplata dynamicznymi, kipiącymi radością i seksualnością ujęciami z karnawału w Rio de Janeiro. Wyszukane stroje z lat 60. i białe twarze gości z kręgów międzynarodowej dyplomacji, finansjery i sztuki kontrastują z kolorową mieszanką ras i tandetnymi transgenderowymi strojami tańczących na ulicach ludzi. Od czasu do czasu widzimy postać samej artystki, przemieszczającej się z motylimi skrzydłami przypiętymi do pleców. Dorosła kobieta przechadzająca się z kolorowymi skrzydełkami nie robi tu na nikim wrażenia — jest jednym z wielu pląsających motylków, Alicją krążącą po Krainie Dziwów, Calineczką, Arielką, skrzydlatą wojowniczką z kreskówek mangi, zagubioną w tłumie dziewczynką z obrazu z Biennale w Sao Paulo, która wędruje do przeszłości, by przeżyć niezrealizowany scenariusz. Jej wyprawa w głąb czasu staje się manifestem wiary w realizację marzeń.

Motyw podróży, również podróży w czasie, powraca w cyklu kolaży Powstańcy 1863-2016. Ich ważnym elementem są XIX-wieczne rysunki autorstwa pradziada Janin malarza, rysownika, uczestnika powstania styczniowego oraz zesłańca – Ignacego Jasińskiego. Prace Jasińskiego przedstawiają akty męskie – znakomite technicznie, ale też ujawniające potrzebę odmiennego spojrzenia na modela – nie przez pryzmat jego bojowej przydatności, ale poprzez jego cielesność, piękno proporcji i nadanie im rysu, który dziś określilibyśmy jako „metroseksualny”. Spojrzenie to niejako przejmuje od Jasińskiego artystka, która klasyczne rysunki łączy z cytatami ze współczesnej pop-kultury – wyciętymi z gazet zdjęciami idoli, będącymi aktualnymi wzorcami męskości – uzyskując tym samym symboliczną władzę nad wizerunkami mężczyzn i odwracając historyczną relację płci w sztuce. W ramach dialogu ze swoim przodkiem-artystą włącza też niewielkie reprodukcje swoich prac oraz zniszczone smartfony, które tak jak piękni mężczyźni z rysunków i fotografii stają się obiektami przeznaczonymi wyłącznie do oglądania. Do „posiadania” wizerunku Janin odnosi się też w instalacji fotograficznej 55, przedstawiającej ciało w ogromnym zbliżeniu, z perspektywy patrzenia na samą siebie. Zamykając we własnej fotografii ten rodzaj spojrzenia, artystka odbiera swój wizerunek patrzącemu. Tworzy w nim napięcie między zbliżeniem i zmysłowością a świadomością przemijania. Z cyklem Powstańcy powiązana jest również rzeźba Biała kruk z pępowiną. Praca ta łączy najnowsze rozważania artystki nad językiem sztuki figuratywnej z jej dostrzeżeniami dotyczącymi pozycji kobiet oraz braku równości w dziedzinie społecznej i kulturowej.

Na wystawie pokażemy też Volvo V70 Cross Country Transformed into 6 Drones (Sands of the Desert) gdzie solidne, rodzinne Volvo V70, analogicznie do wcześniejszego samochodu artystki Volvo 240, uległo transformacji w grupę dronów. Pracę tę można interpretować jako ukazanie cienkiej linii pomiędzy korzyściami a zagrożeniami jakie niesie za sobą postęp technologiczny.

Koncepcja kuratorska wystawy zakłada ukazanie ciągłości w twórczości Zuzanny Janin, poprzez zestawienie najnowszych prac z tymi pochodzącymi z wcześniejszego okresu twórczości.

W połowie lat 90. artystka przeszła do eksploracji własnej tożsamości poprzez poszukiwanie granicy pomiędzy ja i nie-ja. „Ile mnie jest w innych – babce, matce, córce?”, zdawała się pytać w cyklu przenikających się, laminowanych fotografii przedstawiających brzuchy, nogi, ręce, stopy najbliższych kobiet w cyklu Idź za mną. Zmień mnie. Już czas (1995-97). Dziś praca ta zyskuje kolejne znaczenia dzięki prezentacji jej w sąsiedztwie LOST BUTTERLY czy panneau fotograficznego 55.

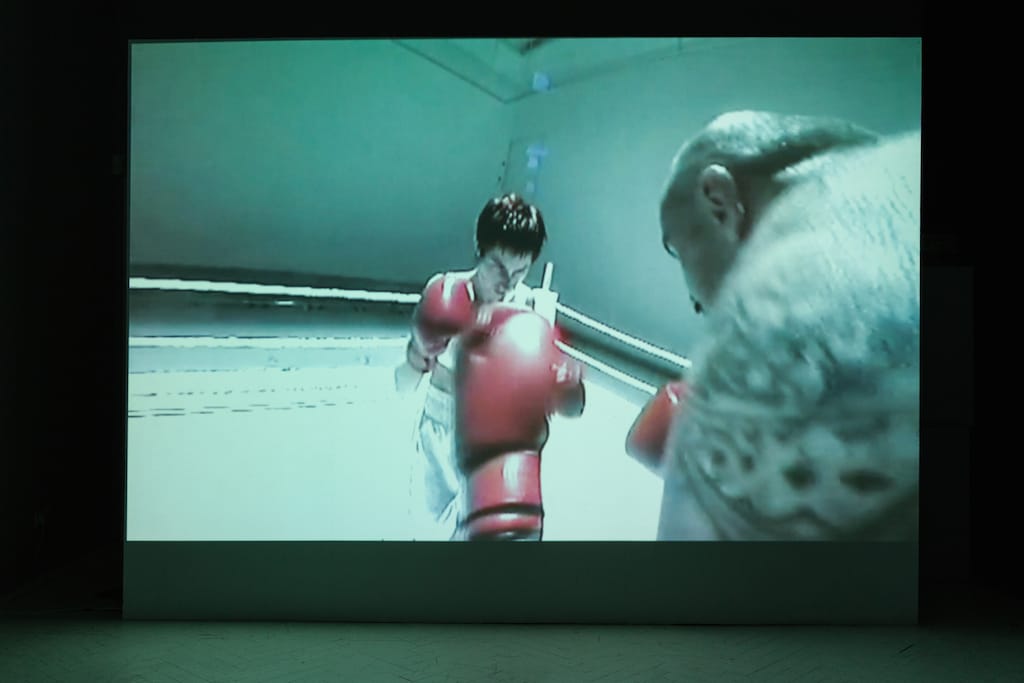

Jedna z bardziej rozpoznawalnych realizacji wideo Zuzanny Janin – WALKA z 2001 roku – pokazuje artystkę w niekończącej się walce bokserskiej z zawodowym bokserem wagi ciężkiej, Przemysławem Saletą. Artystka przygotowywała się do niej, trenując boks przez blisko cztery miesiące. W pracy tej fragmenty walki zebrane są w poetyckim zbiorze zapętlonych gestów i symboli, gdzie typowe zachowania sportowe zostały przetworzone w metaforyczny obraz relacji między symbolicznie przedstawionymi „stronami”. Praca w 2012 roku została poddana digitalizacji, co znacznie wpłynęło na jakość obrazu. Dlatego też pokazujemy ją w nowej odsłonie, ale też w nowej rzeczywistości politycznej i społecznej, która zdaje się pogłębiać metaforę WALKI.

______

ZUZANNA JANIN

White She-Raven

Zuzanna Janin’s second individual exhibition at lokal_30 presents the artist’s latest sculptures, collages and videos alongside her earlier works from the 1990s and the early 2000s. The show coincides with the premiere of a monographic book devoted to Janin’s artistic work, featuring texts by Amy Bryzgel, Magdalena Ujma and Agnieszka Rayzacher as well as an interview by Małgorzata Czyńska.

In the late autumn of 2014, the artist went to Brazil, where she began working on her project LOST BUTTERFLY. It is based on yet another extraordinary story from her biography. At the beginning of the 1960s, Janin’s mother, the Surrealist painter Maria Anto, created a painting for her daughter, who was still in her womb, and portrayed her as a preschooler dressed as a butterfly. Three years later, Ryszard Stanisławski, the legendary director of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, invited the young graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts to participate in the São Paulo Biennial, where he curated the Polish pavilion. The painting never returned to Poland, and the archives of Anto, who died in 2007, preserved a photograph of its later version Zuzanna Goes to a Ball (from 1966), painted for her individual exhibition at the Zachęta National Gallery of Art in Warsaw. More than half a century later, Janin began a journey that followed the traces of the missing work. After two journeys to Brazil, the artist came across a different painting by her mother in the collection of a well-known contemporary art collector, purchased in the 1960s directly from the Biennial. We have already become accustomed to the processual character of Janin’s journey-based works. This aspect is essential also in this case – in her cycle of videos and sculptures. The first presentation of the project at the Labirynt Gallery in Lublin comprised two parts of the film and a series of sculptures, dominated by two works: butterfly wings formed of brass wire and the sculpture LOST BUTTERFLY. A Girl with Onion and Wings (Portrait of the Mother) – a work that conveys a story from the war times and portrays Maria Anto as a small girl rescued from a transport to Auschwitz. The video polyptych LOST BUTTERFLY is a record of the artist’s research that begins in the São Paulo Biennial archives and culminates with a visit to the art collector’s house, where Janin comes across one of the paintings from the cycle exhibited in São Paulo in 1963. The artist develops her own characteristic narrative by interlacing her story and accounts with fragments of other footage. The monotonous action of skimming through black and white photographs, yellowed newspaper clippings is interwoven with dynamic shots of the Rio de Janeiro carnival, which brim with joy and sexual appeal. The elegant white faces and sophisticated fashion from the 1960s sported by the Biennial guests from the international diplomatic, financial and artistic circles stand in stark contrast to the colourful mix of races and kitschy transgender outfits worn by people dancing on the streets. From time to time we can catch a glimpse of the artist herself, who roams the city with butterfly wings fixed to her back. An adult woman with colourful wings is a view that surprises nobody here – she is merely one of the frolicking butterflies, an Alice roaming the Wonderland, a Thumbelina, an Ariel, a winged she-warrior from manga cartoons, a girl lost in the crowd from the painting exhibited at the São Paulo Biennial, who travels to the past in order to live out a scenario that never came true. Her journey into the depths of time becomes a manifesto of her faith in the possibility of making dreams come true.

The motif of a journey, including time travels, recurs in the cycle of collages Insurgents 1863–2016. A major element of the series are 19th century drawings by Janin’s great-grandfather, artist active in painting and drawing, participant of the January Uprising, and a convict sent to a penal colony – Ignacy Jasiński. Jasiński’s works are male nudes, which betray his outstanding skills, but also manifest the need of a different perspective on the models – not through the prism of their utility in combat, but through their bodies and the beauty of proportions, framing them in a way that could today be recognised as “metrosexual”. Janin adopts such perspective from Jasiński as she combines classic drawings with quotes from the contemporary popular culture: newspaper cut-outs with images of idols – the current masculinity role-models. Thus, the artist gains symbolic power over the images of men and reverses the historic hierarchy of the sexes in art. The artist’s dialogue with her ancestor also incorporates small-scale reproductions of her works and destroyed smartphones, which, somewhat akin to the beautiful men portrayed in drawings and photographs, become objects that are suitable only for viewing. The “possession” of the image is addressed by Janin also in the photographic installation 55, which portrays the body in huge close-ups, as seen directly by the person to whom it belongs. By capturing this kind of gaze in her own photograph the artist reclaims her own image from the viewer. Janin builds a tension between the close-up and sensuality as well as the awareness of transience. Another work that bears relation to the cycle Insurgents is the sculpture White She-Raven with a Umbilical Cord. It combines the artist’s most recent reflection on the language of figurative art with her observations pertaining to the position of women and lack of equality in the society and culture.

The exhibition also features the work Volvo V70 Cross Country Transformed into 6 Drones (Sands of the Desert), which transforms a robust family car Volvo V70 into a group of drones, akin to the artist’s earlier car Volvo 240. The work can be understood as a depiction of the thin line between the benefits and threats of technological progress.

The curatorial concept of the exhibition underscores the continuity of Zuzanna Janin’s creative work by juxtaposing her latest works with those from the early period of her practice.

In the mid-1990s, the artist proceeded to explore her own identity by seeking the boundaries between the self and the non-self. “How much of me is there in others – in my grandmother, mother, daughter?” – Janin seemed to ask in the cycle of mutually overlapping, laminated photographs of the bellies, legs, hand and feet of her closest female relatives in the cycle Follow Me. Change Me. It’s Time (1995–97). Today, that series acquires new meanings when presented beside such projects as LOST BUTTERFLY and the photographic panneau 55.

One of the most famed video works by Zuzanna Janin – FIGHT from 2001 – shows the artist engaged in a never-ending boxing match with a professional heavy-weight boxer, Przemysław Saleta. In order to carry out the project, the artist undertook preparations that lasted for nearly four months. The work embeds the elements of fight in a poetic collection of looped gestures and symbols, where typical behaviour on the boxing ring is transformed into a metaphorical image of life and relations between the symbolically determined “sides.” In 2012, the video underwent digitisation procedures, which have largely enhanced its visual quality. For this reason, we are presenting the work in a new version, but also in a new political and social reality, which seems to offer the metaphor of FIGHT a more profound dimension.